By Tonto National Forest Hydrologist Kelly Mott Lacroix

Intro by the National Forest Foundation

Pine Canyon looks like an oasis after driving through the arid Sonoran desert in Arizona. The green forested canyon widens closer to Pine, AZ, named after the ample ponderosa pine trees and Pine Creek that starts high in the canyon and feeds into the Verde River Watershed. Unfortunately, this beautiful canyon is at significant risk of wildfire, which, given its overgrown forest structure and steep topography, exacerbates the potential for impact on the local area, the water source, and downstream communities.

To address these issues, the National Forest Foundation (NFF) is working with the Tonto National Forest and many local partners, as part of the Northern Arizona Forest Fund (NAFF), to restore ecological balance to approximately 400 of the steepest, hardest to access acres in Pine Canyon in efforts to prevent severe post-fire flooding that would jeopardize the safety of Pine, AZ and drinking water supplies for communities downstream should a high-severity wildfire move through the area in its current condition. Tonto National Forest Hydrologist Kelly Mott Lacroix, explains how fire changes the hydrological conditions in a watershed and why this project is needed now.

Example of post-wildfire flooding.

Fire Impacts on Watersheds

After a wildfire is contained, the threat to life, safety, and property is not over. Post-fire flooding occurs when areas previously burned receive significant rainfall (like monsoon seasons in the southwest), which can continue to threaten life and safety and cause significant property damage. Unlike the fire itself, where the immediate threat lasts for a few days or weeks, the danger from post-fire flooding and erosion can last many years after the fire is put out. This makes preventing high-severity burns through forest restoration actions even more important. Forest thinning and prescribed burning efforts can lessen the severity of the fire's impact to soils and vegetation and can therefore mitigate not only the immediate danger from the fire but the lingering and significant effects of post-fire flooding.

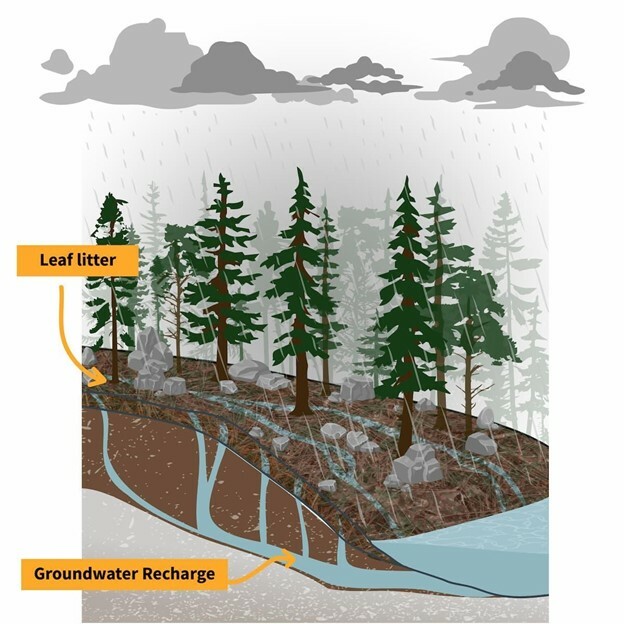

A forested watershed with good hydrologic conditions is one where rain soaks into the soil (infiltration), stream flow response to rain is relatively slow, rainfall is enough to sustain the base flow of a stream, and there is minimal sediment produced.

Healthy hydrological conditions. A forested watershed's ability to absorb and filter precipitation is key to providing enough clean water to residents reliant on this water source.

(Figure from USGS https://labs.waterdata.usgs.go...)

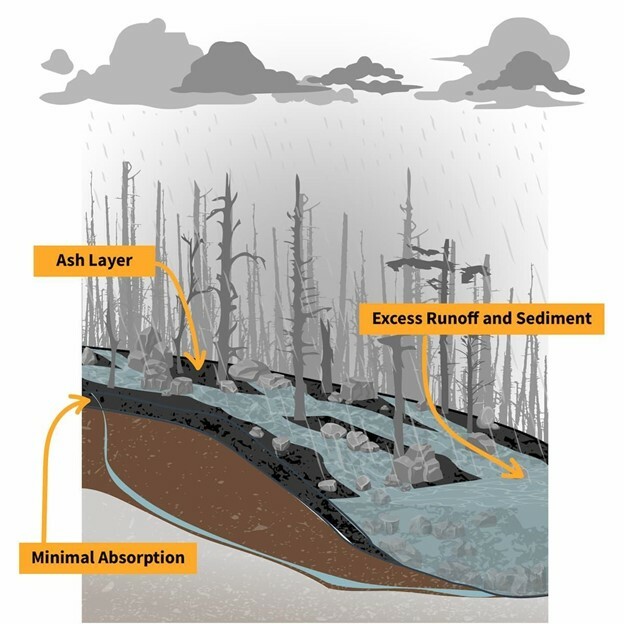

High-severity wildfire impacts infiltration by creating an impermeable layer on the soil that prevents the rain from soaking in. The ground repels water instead of absorbing it, thus increasing the amount of water that runs off the watershed and into streams and reservoirs. High-severity fire also alters hydrologic conditions by destroying forest floor material and vegetation that covers the soil and holds it in place on hillslopes. Without these elements to protect the soil, it is more likely to erode and move soil (sediment) into streams.

After a fire, the ground cover, soil properties, and water flow patterns are all different.

(Figure from USGS https://labs.waterdata.usgs.go...)

Sediment and ash from the fire not only fills pools and reservoirs that create habitat for aquatic life but can also cause water utility providers to spend significantly more money to treat the water before you can drink it. In extreme cases, fires can cause debris flows. A debris flow is a fast-moving landslide — sometimes exceeding speeds of 35 miles per hour — that can destroy everything in its path and carry objects as large as entire trees, boulders, or even cars.

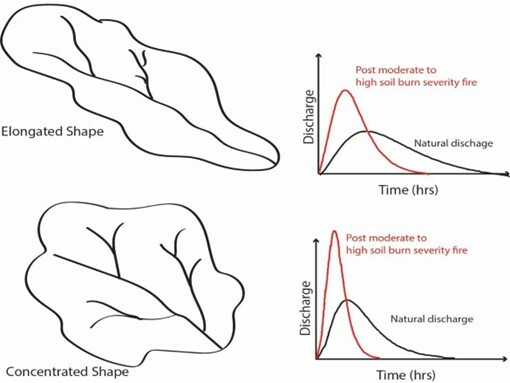

Bringing this back to Pine Canyon and the values of treating these steep slope acres, the watershed above the community of Pine, AZ, is 11 square miles in a round or "concentrated" shape. Watersheds with a concentrated shape experience the most extreme changes in both the timing and magnitude of post-fire flows.

Concentrated-shaped watersheds, like the one above Pine, AZ, see faster water runoff after a fire than elongated watersheds, leading to a higher likelihood of damaging debris flows. (Figure by K. Mott Lacroix U.S.Forest Service.)

Aside from the severity of the fire and the type of soil burned, the other two key elements in determining the impacts from post-fire flooding are:

- The intensity of the rain that occurs

- How soon that rain occurs after the fire

In the southwest, monsoon season usually follows directly on the heels of our fire season. Monsoon rains in Arizona can be very intense and, therefore, more dangerous, especially because the burn scar has had no time for vegetation to regrow or for litter from dead trees to fall to the ground and protect the soil. While we cannot change the shape of the watershed above Pine, nor the intensity of our monsoon storms, we can reduce the risk of post-fire flooding and increase the ability of the watershed to bounce back after a fire. By reducing hazardous fuel loads, and thereby the likelihood of high-severity burns to soil and vegetation, we protect the forest, streams, and watershed.

Everyone benefits from the protection of our watersheds in some way. The Pine Canyon project will prevent flooding and protect drinking water, but other NAFF projects enhance summer camping, winter skiing, boating and aquatic wildlife. We all play a role in how our society interacts with the natural environment on which we all rely.

Sources used to write this article.

- Moody J A, Shakesby R A, Robichaud P R, Cannon S H and Martin D A 2013 Current research issues related to post-wildfire runoff and erosion processes Earth-Sci. Rev. 122 10–37

- Sheila F Murphy et al 2015 The role of precipitation type, intensity, and spatial distribution in source water quality after wildfire Environ. Res. Lett. 10 084007

- Robichaud, Peter R.; Ashmun, Louise E.; Sims, Bruce D. 2010. Post-fire treatment effectiveness for hillslope stabilization. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-240. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 62 p.

- USGS FAQs – What is a Debris Flow https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-a-debris-flow?qt-news_science_products=0#qt-news_science_products

- USGS – How Wildfires Threaten US Water Supplies https://labs.waterdata.usgs.gov/visualizations/fire-hydro/index.html#/

Cover photo by Michael McNamara.

--------

Did you learn something new in this blog post? We hope so! The ecology that binds together everything on our National Forests is a fragile web, and we at the NFF are committed to doing all we can to ensure the healthiest forest ecology we can. To do so requires the support of caring individuals like you. Will you join us to ensure this critical work continues? Simply click here to join with thousands in this important work. Thank you!