Since professional forestry began in the early 20th century, our cultural narrative about who cares about, works on, and belongs in America’s forests has been dominated by white men. And yet, the first Black professional forester was one of the first men of any race to graduate with a forestry degree in the United States.

Black Americans’ relationship with public lands have long been overlooked in the story of land management. But Black Americans have always contributed to the stewardship of forests and grasslands – as conservationists, foresters, firefighters, and leaders.

Photograph of Ralph Brock from the Forestry Education in Pennsylvania collection at Mont Alto Campus Library, Penn State Mont Alto.

Black people have been part of the story of American forestry from its beginning. In 1898, the Biltmore Forest School in North Carolina became the nation’s first school for the scientific study of forestry. Only eight years after the first forestry school was founded, and only one year after the U.S. Forest Service was born, in 1906 Ralph Brock became the nation’s first Black professional forester when he graduated from Pennsylvania’s new State Forest Academy. In his brief career in forestry, Brock helped found the state’s first forest nursery at Mount Alto, had his research published by the Pennsylvania Forestry Association, and gave two lectures at the first Convention of Pennsylvania Foresters in 1908.

Although his public career was cut short by the relentless racism of the white students at the Academy, Brock continued the work he loved in the private sector, starting his own nursery business in Philadelphia. Brock wasn’t the only one - in 1910 Black Americans owned 195 timber companies and comprised about twenty-five percent of all employees in the forest industry.

Integrated Civilian Conservation Corps Camp on the Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia in 1933 before a later decision was made to segregate the camp. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service.

During the Great Depression, more than 200,000 Black Americans participated in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to improve America’s public lands, forests, and parks. Although their opportunities were limited by discrimination, segregation, and abuse from their white officers and peers, Black corpsmen made significant contributions to the nation’s public lands. On the Cleveland National Forest in California, Black corpsmen ran telephone lines between remote Forest Service offices and nearby towns, and in the East, Black corpsmen at Camp Pomona constructed roads and trails that helped establish the Shawnee National Forest in Illinois.

555th Parachute Infantry Battalion parachuting into a forest in Oregon to fight a wilderness fire caused by Japanese balloon bombs in 1945. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service.

A troop carrier plane shuttles parachutists from the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion to the scene of a remote fire in Wallowa Forest, Oregon. Photo from the National Archive.

Made up of all Black soldiers, during World War II the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion (nicknamed the Triple Nickles) played a critical role in protecting the nation’s forest land. In 1945, the Triple Nickles were assigned to the Pacific Northwest where they trained with the Forest Service to fight forest fires caused by Japanese balloon bombs. During Operation Firefly, the Triple Nickles answered 36 fire calls and made more than 1,200 individual jumps - pioneering the field of smokejumping.

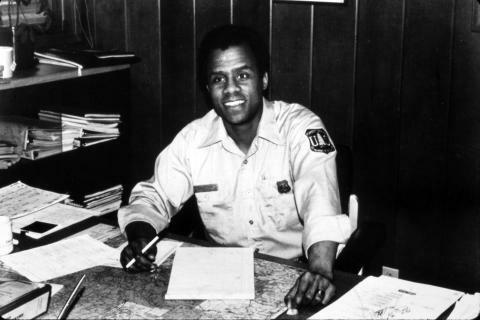

Charles "Chip" Cartwright in his office on Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service.

In 1970, Charles “Chip” Cartwright became one of the first Black foresters in the Forest Service. In the years that followed, he would become the agency’s first Black district ranger, first Black forest supervisor, and first Black regional forester. In a 2021 interview with Virginia Tech, Cartwright said about his many promotions “I learned to believe in myself, and I learned to open myself up for others who also believed in me. And the accomplishments that I made? They were not only for me, but they were for others as well.” In 1998, he was succeeded by Eleanor “Ellie” Towns, the first Black woman regional forester.

And in 2021, after four decades in natural resource management, Chief Randy Moore became the first Black American to lead the U.S. Forest Service. To celebrate, we sat down with Chief Moore and asked him about his time serving in the Forest Service.

The conservation field still has a long way to go to reflect the communities it serves. Less than three percent of foresters and conservation scientists today are Black, and systemic inequities still make it difficult for many Black communities to access the outdoors.

Despite these challenges, Black Americans have always cared for and contributed to the stewardship of National Forests – through their courage, perseverance, compassion, and leadership – and continue to forge spaces where Black communities can find meaningful connections with each other and public lands.

Sources and Additional Resources

“Conservation Scientists & Foresters.” Data USA, Datawheel & Deloitte, https://datausa.io/profile/soc/conservation-scientists-foresters. Accessed Feb. 2024.

Fikes, Robert. “Ralph Elwood Brock (1881-1959).” Black Past, 30 Nov. 2022, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/people-african-american-history/ralph-elwood-brock-1881-1959/.

Goldman, Ben. “Ralph E. Brock, Forester.” Earth Archives, Pennsylvania State University, https://eartharchives.psu.edu/2020/04/13/forestry/.

Hendricks, R.L., and James G. Lewis, “A brief history of African-Americans and forests.” International Programs, vol. 25, 2006, https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/A-Brief-History-of-African-Americans-and-Forests.pdf.

McNeil, Ashley. “Moving Forward Initiative: The African American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps .” The Corps Network, AmeriCorps, https://corpsnetwork.org/moving-forward-initiative-the-african-american-experience-in-the-civilian-conservation-corps/.

“Remembering Chip Cartwright.” U.S. Forest Service, 22 Feb. 2023, https://www.fs.usda.gov/inside-fs/memorial/remembering-chip-cartwright.

“Shawnee National Forest Collections Rehabilitation.” Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, https://cai.siu.edu/curation/shawnee.php.

Sosbe, Kathryn. “Black History Month Reflects on the Past While Peering into the Future.” U.S. Forest Service, 26 Feb. 2021, https://www.fs.usda.gov/features/black-history-month-reflects-past-while-peering-future.

“The CCC on the Cleveland NF and Local African American History.” U.S. Forest Service., https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/cleveland/learning/history-culture/?cid=fsbdev7_016650.

“The Triple Nickles: A History of Service, an Enduring Legacy.” U.S. Forest Service, 19 Feb. 2020, https://www.fs.usda.gov/inside-fs/delivering-mission/excel/triple-nickles-history-service-enduring-legacy.

--------

Cover photo by the U.S. Forest Service.

Every day, the NFF works to help make our forests – and the experiences people have on them – relevant to ALL Americans. We tell stories, highlight historical contributions of all peoples, explore forgotten legacies, and much more. This growing part of our mission requires unrestricted support from people like you. Will you join us today? It’s easy: just click here and offer your support. We thank you!