When Lance Williamson was growing up in the early ‘70s, he’d fish, camp, and explore Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, a 9,000-square-mile spit of temperate rainforest jutting down from Anchorage into the Gulf of Alaska.

“I remember camping in friends’ front yards with views of the sea,” Williamson said.

He lived in Hope, a small community of 50-odd people in a larger-than-life setting: to the north, the dramatic shoreline of Turnagain Arm; to the south, dense forests of Sitka spruce and mountain hemlock; and running through the center of town, Resurrection Creek, which flowed out of the West Kenai Mountains.

Despite the surrounding bounty, Williamson said the creek was “devastated” for as long as he could remember. The site of one of Alaska’s first gold rushes, Resurrection’s gilded banks drew fortune-seekers from all over the world in the late 1800s. By the turn of the 20th century, thousands lived in Hope Mining District.

The creek, previously a lifeline for the surrounding ecosystem, became a lifeline for just one interest. Miners used hydraulic and heavy-equipment placer mining, including with water pumps and excavators, to remove soil from creek beds, straighten the waterway, and block its path from the existing flood plain.

“Historically, there were huge king salmon runs here,” said Williamson, who spent much of his life in Hope and is now retired. He remembers old-timers’ tales of such plentiful kings that residents used them as dog food. But within only decades of the industry’s establishment, that vital population disappeared, and with it much of the diverse ecosystem that relied on it.

The creek remained like this for nearly a century, until one spring day in 2006, the fish began to return; all at once, in staggering numbers.

First came the mighty king, a species found in few other streams in the area. Not long after, the speckled chum and the diminutive pink salmon, and eventually, the dark-metallic coho and prized sockeye. The water, otherwise deep green and gray, flashed pink with fish, running two per square foot of water. They rested in newly dug pools and spawned in freshly laid gravel beds. And the following year, in 2007, their populations increased sixfold.

“The water, otherwise deep green and gray, flashed pink with fish, running two per square foot of water. Salmon rested in newly dug pools and spawned in freshly laid gravel beds.”

These astonishing returns were evidence that a project led by the Forest Service to restore 15 miles of Resurrection Creek had been a success. Despite this resounding impact, lack of funding put the project on hold, and more than a decade passed before more work could be done.

The NFF’s Chief Conservation Officer Marcus Selig and Pacific Northwest and Alaska Director Patrick Shannon viewing in-stream work at Resurrection Creek. Photo by Janessa Anderson.

“We knew that without active and ongoing restoration, this prime habitat would never return to what it once was,” said Kenzie Barnwell, the NFF’s Chugach Stewardship Coordinator for the Chugach National Forest.

Now, thanks to an unlikely set of alliances, restoration work at Resurrection Creek is again underway. Slated for completion in 2026, the project’s second phase will rebuild 2.2 miles of waterway and 74 acres of riparian habitat. In a first-of-its-kind partnership for Alaska, conservation nonprofits and mining companies have joined to help heal the damaged river.

On a bluebird day in August, at the tail end of a salmon run that saw Resurrection Creek’s waters again turn scarlet red, engineers and excavators worked side-by-side along the river banks. As before, the team is building features crucial for salmon to navigate and spawn during their freshwater life stages: reconnecting the historic floodplain; constructing new pools and ponds; installing logs and root-wads in new stream channels, and revegetating the adjacent wetlands.

A restored stream channel completed during phase two. Photo by Janessa Anderson.

A heavy equipment operator working in June 2023. Photo by Janessa Anderson.

Before long, this work site will resemble the sinuous stretch of creek, restored during phase one, where, at the height of the recent salmon run, a young bear was spotted fishing in newly formed ripples that brimmed with fish.

Brian Bair, the Forest Service Watershed Restoration project lead who has been involved since Phase I of the project, described how having a successful blueprint has been a balm in the face of such a large-scale endeavor.

“Fish are the best critics”

“Fish are the best critics,” said Bair, pointing to a run of pink salmon, whose population numbers have increased tenfold since 2005.

Though the environmental review for the project’s second phase was completed in 2015, a lack of funding and resources caused the lengthy delay. Things changed in early 2021, when an infusion from the Alaska Abandoned Mine Restoration Initiative, an unusual collaboration between conservation nonprofit Trout Unlimited (TU) and mining company Kinross Alaska, reinvigorated the effort. To ensure a multi-year, phased project, the NFF raised an additional $7.1 million dollars in state, federal, and private dollars, including from the Department of Commerce, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Transformational Habitat Restoration and Coastal Resilience Grant.

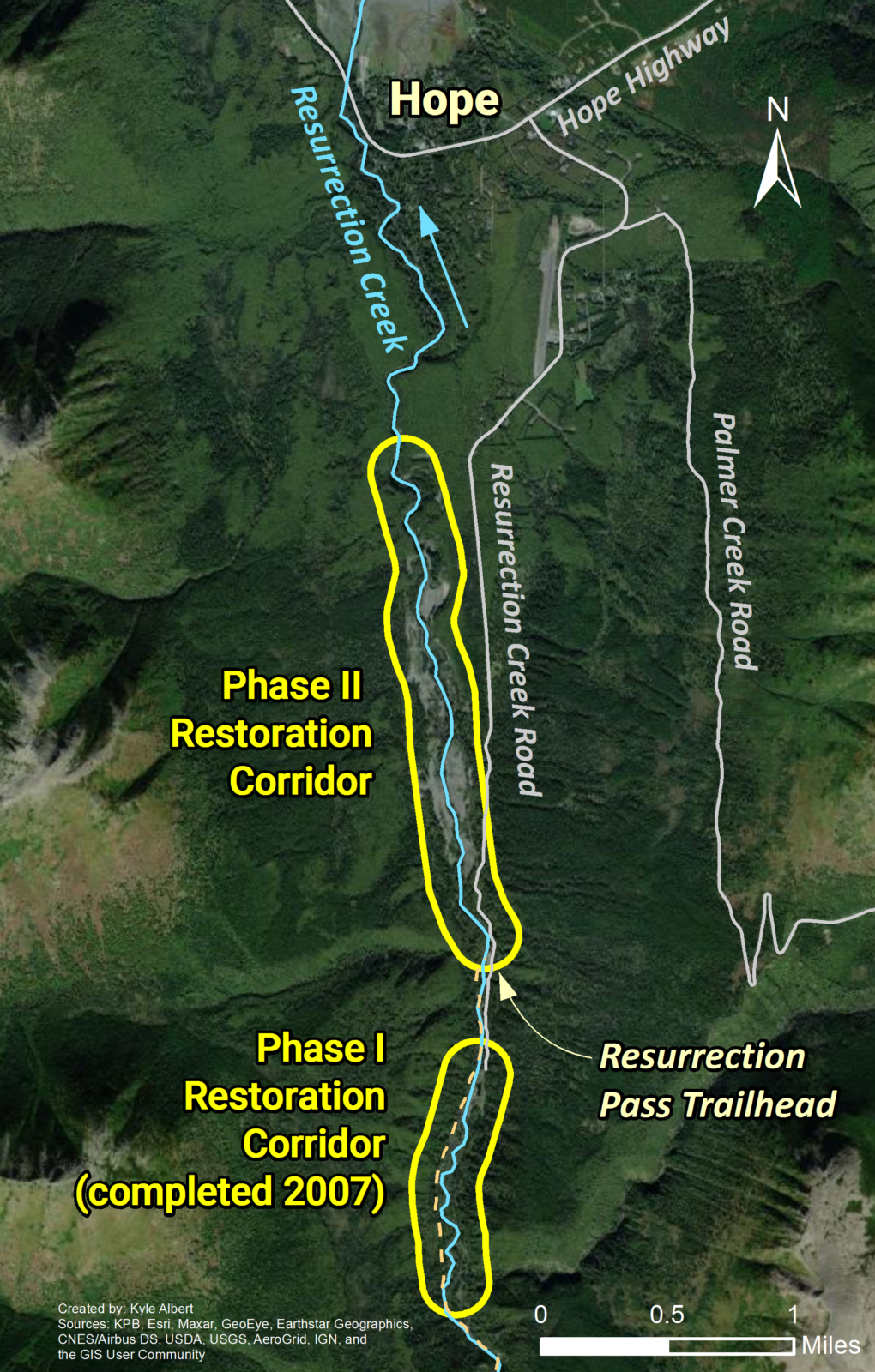

A map depicting phase one and two restoration efforts. Credit Trout Unlimited.

For TU, part of the venture’s appeal was its accessibility. “Some restoration projects are in remote places, but this is where many kids go to catch their first salmon,” said Marian Giannulis, communications director for TU’s Alaska Program.

These are not the only unlikely bedfellows here. The 130-year-old Hope Mining Company is still actively mining on private inholdings across the phase two’s restoration area. To create a working corridor, the NFF and Forest Service established an agreement with the mining company to allow restoration work to occur alongside mineral extraction. The scene is as uncanny as it sounds: to one side, Forest Service excavators moving earth to create new creek bends; on the other, mining excavators moving earth for gold.

“The original miners turned [the creek] into a straight ditch, which was great for mining, but horrible for habitat in one of the most beautiful valleys in the country,” said Hope Mining Company Vice President Jim Roberts. Unlike at the height of the industry, only a few operators actively mine the area today.

Moving boulders and harvested logs to create crucial salmon-spawning habitat. Photo by Janessa Anderson.

“The impact on the environment is not nearly what it was,” said Barnwell, the NFF’s stewardship coordinator.

Williamson, who grew up in Hope, returned to the seaside town a few years ago after retiring from a career in construction, landscaping, and critical habitat restoration. Having kept a home in Hope for 50 years, he’s watched the community morph over time, from a place driven exclusively by mining interests to one sustained by outdoor tourism, from a quiet town of a few dozen people to a recreation hub whose population fluctuates with the seasons, and ultimately, from a vestige of the gold-rush era to the site of cooperation that will set precedent for future conservation initiatives across the state.

“I grew up in an era when you were on either this side or that side,” said Williamson. “At this point in my life, I’ve realized that to get beyond what’s stopped most of this environmental movement, you’ve got to work together.”

Reporting contributed by Joe Yelverton.

Hike or backpack the 39-mile Resurrection Pass Trail, which begins along the creek near the town of Hope, in Alaska, for a firsthand look at the dynamic ecosystem benefiting from the NFF’s Resurrection Creek Restoration Project.

About the Author

Erin Vivid Riley is a writer, reporter, and editor whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Condé Nast Traveler, and The New York Times. Before going freelance, she was an editor at Departures and Outside.

Cover photo: Alaska’s Resurrection Creek flows from the West Kenai Mountains. Photo by Janessa Anderson.