Less well known are the historic sites the Forest Service owns and cares for. Two such places stand out, although they could not be more different from each other: one, a grand château high above the Delaware River in northeastern Pennsylvania, designed by an esteemed Gilded Age architect and displaying fine European craftsmanship. The other, 2,800 miles due west, a rustic but grand lodge in Oregon’s Cascade Range built by federal work crews during the depression and adorned by Native American art and exquisite carving.

Respectively, Grey Towers and Timberline Lodge are beloved American icons, each distinguished by their designation as National Historic Landmarks, the top tier of official recognition for historic significance. They also share a deep and lasting tie to the Forest Service.

From Wallpaper to Well Managed Forests

Built to reflect its owners’ French roots, Grey Towers was the imposing summer home of James Pinchot, a wealthy wallpaper manufacturer and lumberman, and his wife Mary Eno Pinchot. They hired renowned architect Richard Morris Hunt to design a château-style mansion set on extensive grounds, an estate that quickly became the dominant feature of Milford, Pennsylvania, a small town along the Delaware River. With 43 rooms and three tremendous turreted towers, the landmark was built from indigenous fieldstone and immediately became a gathering place of the wealthy and important.

In 1875, when James Pinchot selected the site for his estate, it was essentially a denuded hillside; only decades later would it resemble today’s verdant appearance. That would be true of much of the eastern United States. In the late nineteenth century, these lands were utterly cut over and simply left bare save hundreds of thousands of stumps. Pinchot came to recognize the unsustainability of such practices, even though they had personally enriched his family, and he saw in his son Gifford an opportunity to begin righting the extremes of his own generation.

"How would you like to be a forester?" James asked Gifford, invoking a profession that didn’t even exist in America at the time.

"I had no more conception of what it meant to be a forester than the man in the moon....But at least a forester worked in the woods and with the woods—and I loved the woods and everything about them.”

With no school of forestry in the U.S., Gifford enrolled in the French National School of Forestry before returning home to attend the new Yale School of Forestry, conveniently funded by his parents.

It was propitious that the tremendous château in Milford opened on the young Pinchot’s 21st birthday, an event marked by the father presenting the son a copy of George Perkins Marsh’s Man and Nature: Earth as Modified by Human Action. Considered the foundational text of a nascent conservation ethos, Marsh’s book made the case that stewardship was essential to progress. This idea defined Pinchot’s vision and career. In 1905, he was appointed by his friend Teddy Roosevelt as the first Chief Forester of the brand new U.S. Forest Service. The Forest History Society has noted that: “[Pinchot] had a strong hand in guiding the fledgling organization toward the utilitarian philosophy of the ‘greatest good for the greatest number.’ Pinchot added the phrase ‘in the long run’ to emphasize that forest management consists of long-term decisions.”

Photo courtesy of the Grey Towers Historic Association.

Grey Towers became the intellectual center of forest thought in the early twentieth century. From 1901 to 1926 it was the primary summer fieldwork location for the Yale School of Forestry. In 1903, the elder Pinchot started the Milford Experimental Forest as a lab and learning site. Leading thinkers and practitioners gathered to share ideas and questions about the rapidly growing field of professional forestry, including coming to terms with the abusive and unsustainable logging practices of the day.

Blacksmiths, Stonemasons and a “Magic Mile”

Standing at 5,690 feet elevation, the literal timberline, the majestic lodge of the same name was built by Works Progress Administration crews between 1936 and 1938 as part of the massive federal effort to jolt a depressed nation back into economic health.

Gracing Mt. Hood National Forest an hour east of Portland, Oregon, Timberline boasts a lobby with six stone fireplaces joined by a huge chimney rising 80 feet through the hexagonal room. Awed visitors enter through an 1,800-pound Ponderosa pine front door and encounter carpentry, metalworking, masonry and carving throughout. Some have referred to the lodge as a veritable museum of uniquely American rustic decorative arts—table legs and Newell posts are carved with beavers, rams and owls, wildlife all found in the surrounding forests.

In 1935, lacking funds to hire a private architectural firm, the Forest Service gave the task to a team of four in-house architects led by Tim Turner. Each had grown up in the Pacific Northwest and brought a strong sense of the region’s innate character to their plans. By all accounts, this team produced a world-class design suited to its demanding climate, reflective of the ‘everyman’ ethos that built it and respectful of the native heritage and ecological history of the region.

The lodge and its leisure time offerings were something of an experiment in the Forest Service’s ability to promote outdoor recreation. Franklin D. Roosevelt noted that this “venture” project would “test the workability” of the government’s ability to own and operate such places. This flirtation didn’t last long as Timberline’s operations were almost immediately contracted out to a private concessionaire under a special use permit granted by the Forest Service and have been thus ever since. Nevertheless, the ties with Mt. Hood National Forest were then and remain integral to the resort.

While America’s downhill ski industry was in its infancy in the 1930s, it was about to take off, in part thanks to Timberline’s innovations. The year it opened, the resort installed the “Magic Mile,” a mile-long chairlift that ascended to 7,000 feet. Operational by 1939, the lift opened up tremendous new recreational possibilities. It was only the second passenger chairlift in the world; a few years later, the resort opened an aerial tram to serve growing crowds, though it closed in the 1950s.

A mere 17 years after opening, the entire celebrated Timberline enterprise was on the rocks and ultimately ceased operating. Within months of its closure, Oregon businessman Richard L. Kohnstamm took over as the area operator and dedicated the rest of his life to the landmark resort, returning it to profitability and earning the sobriquet “the man who saved Timberline Lodge.” His son, Jeff Kohnstamm, succeeds him as the area operator to this day.

Encounters with Presidents

Each of these sites bears a special relationship with a U.S. President. Timberline owes its very existence to the works program FDR put in place as one of many mechanisms to pull America out of the Great Depression. On September 28, 1937, FDR’s 40-car motorcade ascended Mt. Hood for the president to dedicate the new building. That day, he reiterated the twin themes that define and often stress the Forest Service even today: timber productionand recreation. First, he noted how future visitors to Timberline could “visualize the relationship” between National Forest lands and economic recovery. They would “understand the part which National Forest timber will play in the support of this important element of northwestern prosperity.”

Roosevelt also correctly presaged an era of growing recreation on forest lands.

“Those who will follow us to Timberline Lodge on their holidays and vacations will represent the enjoyment of new opportunities for play in every season of the year.…Summer is not the only time for play….[People] are going to come here for skiing and tobogganing and various other forms of winter sports.”

Today, things have come full circle from Roosevelt’s time as U.S. ski resorts are rapidly retooling to offer summertime activities (such as ziplines and mountain biking) to balance their wintertime high season long dominated by skiing. With more than 60 percent of western ski areas on Forest Service lands, these changes also reflect the ever evolving role of these public lands and their multiple uses.

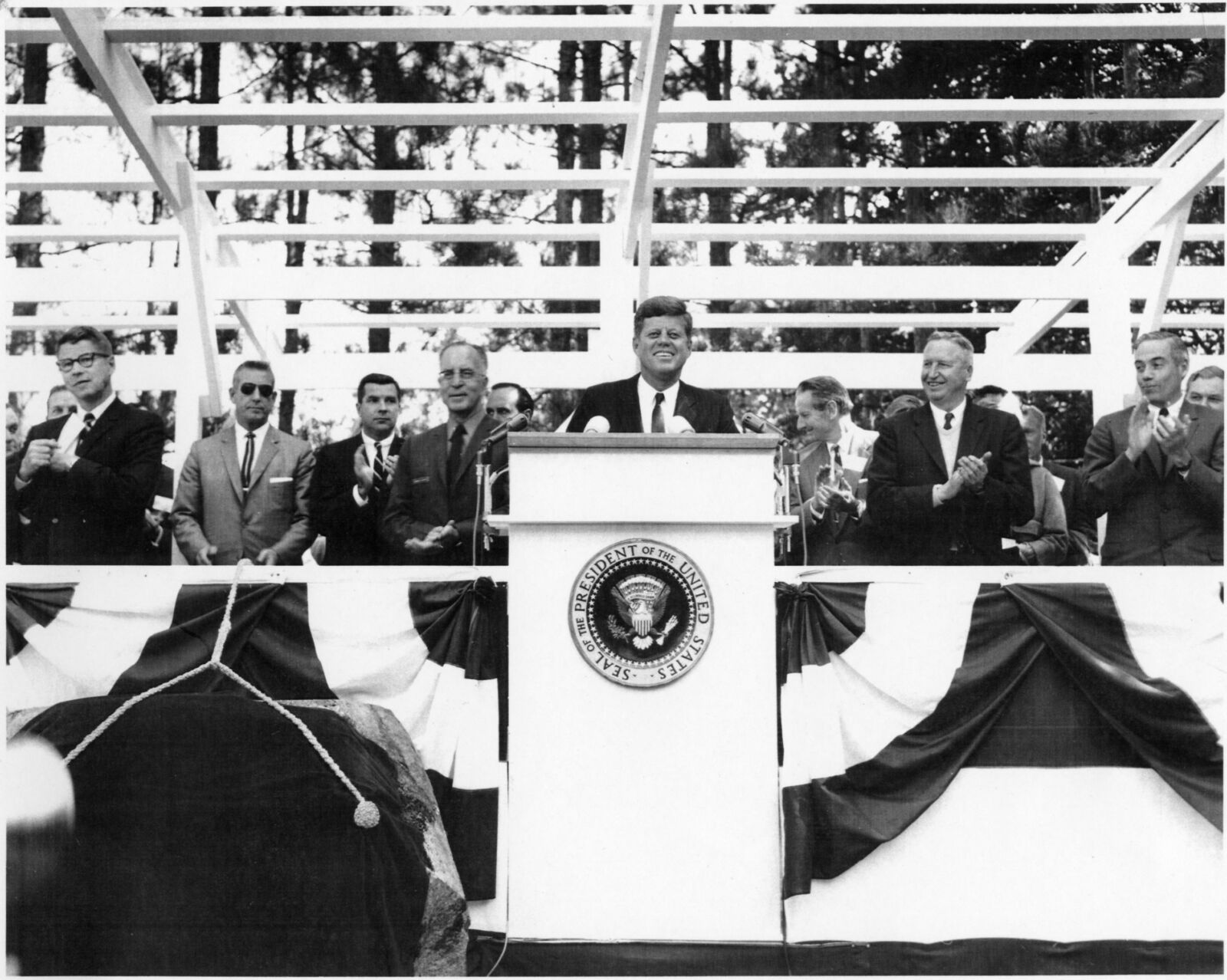

Twenty-six years, almost to the day, after FDR dedicated Timberline, President John F. Kennedy visited Grey Towers. With tiny Milford abuzz, the president helicoptered in for a brief ceremony to accept the Pinchot family’s estate as a gift to the entire nation. On that early fall day, Kennedy’s visit coalesced three notable events. First, the official transfer of the mansion and 101 acres of surrounding land to the Forest Service; second, the launch of a new Pinchot Institute for Conservation Studies at Grey Towers, a nonprofit organization still active today in forest policy and research; and finally, the kickoff of Kennedy’s national “conservation tour.”

Over the next five days the president visited 11 states and made 15 speeches about the need to protect America’s natural resources. Kennedy’s stumping for the environment was surprising; he had shown little interest to date in the outdoors. Yet, Rachel Carson had published Silent Spring the prior year, and national cognizance of early environmental issues was rising quickly. The tour was Kennedy’s last major opportunity to summon the nation’s attention for conservation as he was assassinated two months later.

PRESSING FORWARD WITH A CONSERVATION MISSION

Both Grey Towers and Timberline draw their character and reputation from strong historical associations. Yet, each is also a vital agent in continuing to educate and inspire Americans to enjoy and protect their National Forests. Timberline welcomes two million people annually, actively informing guests about its symbiotic relationship with the National Forest that rings it. Its birth as a public works project and showcase of the richness of nearby flora and fauna give the resort an intimate tie with the ongoing mission of the Forest Service.

Grey Towers’ tours, seminars and events focused on forest history, theory and practice continually rekindle the questions Gifford Pinchot doggedly pursued as America’s first chief forester. The place itself, a grand nineteenth century gesture, bears witness to a legacy of seeking the most enlightened approach to managing our forests. At the same time, Grey Towers represents and embraces a remarkable sweep of changes in our understanding of forest stewardship, changes that will certainly continue to unspool throughout the twenty-first century.